The questions posed in the opening topline article were:

Can you identify which riders are helping to improve their horse’s toplines, which ones are not?

Can you identify what rider changes would help the horse be able to move more correctly?

Can you identify which horses are fighting significant conformation challenges?

Which ones are likely suffering injuries?

Which ones are just suffering bad riding?

What else pops out at you when looking at the pictures and comparing them to each other?

The first question is easily answered without looking at the sample set of horses, or any horses for that matter. What often makes a gaited horse soughtafter is the smooth ride it offers. By tightening its back and swinging its legs in various timed gaits, the horse eliminates any need for the rider to have a supple lower back to avoid bouncing like a sack of potatoes. Great for ease of ride and great for rider comfort, especially if suffering from certain injuries. Not so great for the horse. It’s hard to find a gaited horse that isn’t displaying the negative effects of being a hollow-backed leg mover. Adding speed (see article: Speed Kills) to the gaiting increases the negative factor for the horse. Saddleseat horses are often not gaited, unfortunately the exaggerated chairseat of the rider with horse’s head pulled up to the sky by huge shanked bits does the exact same thing to the horse as gaiting. Current conformation trends in many gaited and saddleseat horses, like over-angulated hind legs via excessive tibia length, make it that much easier for the horse to hollow its back.

It is imperative that these horses are regularly cross-trained with a specific focus on non-showing frames and non-gaiting gaits. Plenty of long and low, groundpole and cavelletti work, stretching, massage and all exercises that promote true and real engagement to counter the ill effects of constantly carrying a rider around on the forehand with a hollowed back, base of neck dropped, and hocks trailing. I can hear the shouts from people, ‘Doing that will ruin the horse and its ability to gait and perform correctly for shows!’. Um…yeah…NO, IT WON’T. Jumping a horse never stopped if from being able to do a piaffe, cut cattle, or jog slower than I crawl backwards. I’ve cross trained gaited horses. They all physically and mentally thrived on the variation in work. The result was an improvement in their gaiting.

Keeping the above in mind, let’s take a closer look at our sample horses 1 thru 8 & 8a.

The first three horses are Icelandics, as everyone guessed. Rather than repeat the great information posted by jrga, see her comments below which I’ve italicized. I added a couple of small comments.

jrga posted: To address 1-3, without researching to make sure, I would say the first three are Icelandics tolting in the fastest gait, basically the equivalent of racing. Given what we’ve covered about the difference between racing and riding, one would not expect to see the roundness, lifting of the base of the neck, impulsion, etc. of collection at this gait. Speed is inimical to collection and vice versa. Collection asks for energy upward, racing asks for energy forward to cover ground.

Icelandics are not particularly uphill, they are all around horses, meant to carry great weight, act as drafts and for riding. As ponies, they are known for their stoutness, short backs, strong backs – meaning well place LS joint – breadth across the back, and of course you get a short neck not inclined to a graceful arc with those goals. But you did get an animal that should eaily develop a double back and still show good muscling.

I love the little grey, the rider, like most gaited horse riders tends to be at the back of the saddle and a little braced, short rein that does not encourage any roundness, but this rider has given more rein to let this little guy stretch and uses a snaffle, not a big long shanked bit as an ASB or TW might be toting in America. Further the rein passes above the base of the neck which would allow rounding more easily if they weren’t moving at speed. The horse is not particularly broken back in the neck, but does show enough muscling under the neck to indicate that he spends some time that way. He is fairly deep at the loin girth, a sign of the back strength, and has coiled his loin to the maximum. His ungrounded hind foot shows one of the maxims, the lower joints of the leg reflect coiling of the loin, the lower joints can’t close more than the SI but if operating correctly (ie, without injury or bad tight muscles in the butt) will close as much. This guy has a small butt, looks fairly smoothly muscled with some tightness in the cats, but for such a short legged guy with a little butt, that foot is going to meet its maximum potential to reach forward and hit the ground and push while still under the butt to some degree. If the rider were a touch better balanced over his/her feet and closer to the withers, and varied his work routine to include suppling and rounding with this guy, the couple of small issues of tightness in the cats and the undermuscling would be improved and that would probably improve the other gaits that are not intended to be racing gaits.

I think jrga was being kind about the rider’s position. He’s collapsed his core, rounded his shoulders, broken his wrist with the left hand held higher, tipped his weight into his toes and has his butt hanging over the back of the saddle, which I feel is placed a bit too far back, such that he’s pretty much sitting right over the loin. But he has been kind to the pony’s mouth.

What I want people to most understand here is that despite the gaiting, the speed, and the rider position – none of which help the pony to develop physically to protect itself – this pony exhibits minimal issues because it’s just so solidly built. Its conformation is looking after it for the most part. Just some basic changes in the day to day training routine to, as jrga says, supple and round would have this individual in optimum muscular health.

The second horse (dark bay or seal brown), whatever his coat color would be called, is a slightly different angle, but I would say at this moment, a tiny touch less broken back than number 1 as a matter of everyday riding, though still the characteristic heavy short neck that isn’t going to look like a pretty rainbox arc of an Arab on its best day. Again all the same breed characterisics, wide, broad build, deep through the loin girth. Maybe a little bit tight towards the rear of the glutes. Showing excellent reach and a touch more balance toward the collection continuum, note the hind foot has left the ground, not even the toe is grounded out behind the horse, pushing less, going up more. The outside hind is going to ground about the same time as the inside fore leaves the ground, there could be a tiny moment of suspension, the hind will also be well placed up under the body, the outside hind also differs in the angling of the leg, it will land slightly more to the inside of the body shadow, typical of a slight bit more roundness (not ‘collected’ but remember we are talking about a continuum from totally hollow to totally rounded up into a mamimum drawn bow look.) The rider is also a little to the back of the sadlle, but overall still better balanced, probably very capable of riding this horse round, and given no absolute horrible hollowness along the top line, though maybe not as fully rounded as the muscling of the loin and glutes could be, probably spends time suppling this horse.

A pony with even better conformation (bigger hip, deeper loin, neck closer to medium in length), and with a rider/trainer who spends some time doing other ‘stuff’ to help the overall health of the pony. The hollowness of gaiting at speed in evident in this photo – flatness in the loin and dropped base of neck – as would be expected, but it’s really quite minor. Someone is doing a great job with this pony.

The major point to take away from this is that doing correct non-gaited training/cross training/ doesn’t harm the individual’s ability to a) gait, or b) be fast, or c) gait and be fast. Indeed, it helps the individual be better and healthier.

The number 3 horse is very hollow at this moment, back clearly dropped. The muscling shows some angularity and tightness, the neck is clearly broken back and the rider has the ‘watersking’ on the horse’s mouth look going. This horse also has the least amount of depth to the loin girth, a weaker structural issue that should be addressed. The rider is well balanced with in him or herself, but again, more back in the saddle and bracing. Could also be we’ve caught a little guy out for a run in the great outdoors who is ‘running away’, but the muscle and loin girth suggest that the broken back neck, running against bit pressure is typical. Nevertheless, the leg position is almost identical to the number two horse, also supporting the idea that this may in fact be one of those rare moments in time where the picture caught a bad moment. If this a young horse, then the muscling may be a little bit juvenile in that he hasn’t been in work long enough to have developed weight carrying ability and the depth of loin girth an older hose would have. So in essence, we see a bit of a contradiction in action, broken back, hollow, some muscling questions, but still the rear legs are moving fairly freely forward to carry weight under the body, though at basically a running gait. Again, a horse that needs more suppling work to insure that he has full flexibility and good muscling over all, while still understanding part of his job his to move at a racing gait.

I agree with the ‘running away’, I think this one is going for all its worth and regularly does so. Best rider positioning of these three, but also the most inverted way of going. Think about that for a second – most balanced riding paired with the most inverted way of going. It’s a contradiction and why jrga was giving some possible reasons why that might occur. Regardless of the reason, this pony would benefit from working in traditional gaits with a goal of suppling and rounding.

The next individual shows another conformation trend (besides the overly long/over-angulated hind leg) we see in a number of gaited breeds – a trend we’re also seeing in non-gaited breeds – that makes life more difficult for the riding horse; the long neck.

Because of the use of leverage bits, the handsiness of people, and the widespread ignorance of how a horse achieves (and should achieve) coming onto the vertical, most people should avoid long-necked horses like the plague. The usual outcome is some form of pretzel, in this case a pinched throat and bulging, over-developed base of neck. Something I do really like about this horse is the cleanliness of his legs/joints.

Once again I copy and paste a portion of a jrga comment addressing conformation of this individual. This looks like a Tennessee Walking Horse, fairly ordinary in the smallish butt (no TB or QH butts by percentage of body length), total hind leg length is long with a little too much in the gaskin by length. But this is a breed choice, the belief is that the horse will move in gait better with that long leg and to a certain extent that is true, but like most human choices for horses in the 20th century, it can be exaggerated. He is long of back, adequate but not great loin, neck too low, point of shoulder could be higher, long in cannon, but again, a typical breed choice, believed to give the high action desired in the big lick walk. Together, not a riding horse conformation. The good things, he is not pulled back into the elk neck, has adequate bone and he has normal feet, no stacks, huge elongated toe, etc.

I can’t stress enough (again) the importance of the wrong breeding choices we make because of a basic ignorance for what traits produce what actions in the horse. We then perpetuate those mistakes by buying these horses from the breeders. And I don’t care if it’s a small time or big league breeder. If there is no market, there is no money to be made, the breeding will stop. Yeah, yeah. I hear you. Conformation isn’t everything, temperament, personality and other intangibles are important. For just one minute consider your body and what you’ve discovered over the years that your body will not allow you to do. Now imagine someone forced you to do that thing you’re body was never built to do, day after day, week after week, month after month, year after year, and during that whole time you had to put up with abuse, intentional or ignorant does not matter in the end. How are you feeling now about a horse not built to effectively or efficiently carry a rider? Thank God for that awesome temperament, eh?

I highly recommend everyone go back and reread jrga’s full comment about this horse and the subsequent conversation about bits (and other things) that ensued.

The next gaited horse (Missouri Foxtrotter if I remember correctly) has found a different way to deal with human handsiness; evade by going behind the hand/bit. Don’t be fooled by the sagging rein, there’s plenty of ‘contact’ going on here via the weight of the split martingale, and this horse has seen plenty of direct hand contact in the past. Note the flatness of the neck directly behind the poll. That’s always a clear indication of forced framing. Why this horse chooses to evade contact in this manner has mostly to do with the difference in neck structure. This horse’s neck is set on a lot higher than horse #4, it’s very Arab-like in its structure. You’ll see many of those swan-necked Arabians with that flat, locked upper neck development.

I also wanted to point out the typical, tremendously exaggerated hind leg length on this horse. Despite that, and the rider imbalance, this horse manages not to trail the hocks in this moment because of the wonderful hip and strong loin. This horse has far more potential than the previous to be able to carry its rider without doing damage to itself.

The next picture is all sorts of wrong. What keeps this horse going is its mostly very strong conformation. The tibia is still far too long, but there’s so much other structural strength that the horse overcomes it. I refer you again to a jrga post where I’ve bolded points I was going to make, those particularly addressing the systematic destruction of the horse – not just this one specifically, but all horses. Don’t ignore the rest of her post. The nuggets of information about the spine, head twirling etc… are invaluable.

Horse 6. The one many felt was painful to look at. Of course it is, which is why we should look all the more closely. Because this is the logical extreme, ie, the worst of the worst of what not to do. Ultimately, you need to look at lots of good so you can imagine yourself in the same body position, same lack of tension, same giving, open posture of body, arms and hands. But first you need to know why this is so horrible, and yet it is the embodiment of the philosophy of many horsemen about how horses work. And it is wrong, wrong, wrong. Yet it is defended, admired and pursued by many. It is unconsciously pursued by many in lesser forms as they seek to hold up a horse’s head, or to make the neck arch through rollkur, or lower the head through devices, or control a horse that gets too strong with heavy hands and stronger bits, to create ‘frames’, to rock a horse back on its haunches like it was a rocking chair on rails, to use a Passoa system to pull its frame together, or any other number of absurdities. Yes, absurdities of thinking that people don’t want to let go of because that is what they saw rewarded in the show pen, or what their first teacher taught them or how they’ve ridden for years and it works pretty good, mostly, except sometimes.

So go back to some old threads with skeletons pictured and re-read them. Study those bones, and think about how they fit together, and how those interior structures, determine how the outside looks, but more importantly, how it will move. Those bones are rigid, the joints supply some flexibility, but they only move so far and, in most cases, in very limited directions. Any time you ask them to move in a way they were not meant to move, you are setting yourself up for failure, failure to achieve fluid movement, failure to get cooperation from your horse, and ultimately, failure of your horse’s health and well being. No one should deliberately choose failure for their horse. No one reading this blog should choose ignorance and, thereby, failure for their horse.

Number 6 is one of the better conformed horses (not perfect, but nicer than most) for riding of all the horses pictured. What is being done to this horse is criminal. It represents every bad idea in horsemanship, except the tie down device that was left off because they can’t be used in the showring, but you know they use it in training.

Look at the spine first. The spine is what you ride, it should be as close to level as the horse’s conformation will allow when you are sitting on it, it should be flexible enough to lift, from the arc of a bow as it is tightened, and then to relax, actually go hollow, as well as bend side to side within the limits allowed by the vertebra. In this case, this horse is built close to level, with minimal training and strengthening of the belly muscles, this horse can easily carry a rider’s weight because it comes naturally to this horse. So where did it all go wrong?

In the most fundamental way it went wrong because the rider rides from a fundamental misconception. A horse doesn’t move like a rocking horse, it doesn’t rise in the front end by its head coming up and back, its back going hollow and its butt going down relative to the head. You can’t rock a horse back onto its haunches. It’s a phrase that gets used, but it is not what happens anatomically, so any attempt to rock a horse back will ultimately fail and the horse will get sore. So lose the thought. Replace it with a new fundamental image.

To create a horse that can carry weight (carry weight) on the haunch and free the forehand from its purpose of carrying most of the horse’s weight at rest, you work with the spine, the whole spine from tip to tip. The spine starts at the atlas where the horse’s head meets the first vertebra. That is the joint in the neck that provides the greatest range of movement and also serves as alock that limits the movement of every other vertebra in the spine. At the atlas the head can move the nose out, tip it up in the air, tuck it back to its neck, turn side to side to a certain extent, and make the most powerful movement of all, to offset the nose slightly and tuck the head/jowls to the side of the vertebra column. Deb Bennett calls it head twirling, others might call it release or a give, it is the position from classical literature in english riding where one sees the eye on the inside of the horse. Why is it the most powerful movement the horse can make? Because it is the movement you can’t take from a horse, he has to give it, but it is the key to unlocking the poll and freeing the rest of the spine to achieve maximal movement in a soft fluid bend side to side, and to lift. You can push and pull the neck into any number of contortions, but it will involve vertebra behind the atlas and you will always be pulling and holding that position, feeling sides like cement even if the horse moves laterally and never get the hind feet to engage and fold and become the loaded springs that carry the weight of the horse on the haunch, freeing the forehand of its normal extra share of weight.

Horse 6 shows a bulge of muscle at the poll, that sucker is locked tight, it can’t release any more without physical therapy. That big old long shanked bit, the rider water skiing with hundreds of pounds of pressure distorting the jaw so the horse looks parrot mouthed, pulling the head back, hollowing the spine, making the legs stiff, look at the fine muscles of the upper legs straining to move feet they weren’t designed to move, causing contortions of the tendons and check ligaments, ruining the horse’s legs, setting it up for injury and pain, damaging the ligaments in the back, and destroying the mind and spirit of the horse. (Making a note here: I blew the picture up and I don’t think the horse has a bit in its mouth, I think it’s a hackamore. That doesn’t change anything about what’s been said.) And we don’t even have to mention how cruel and useless those weighted feet are and how they multiply all the negative affects just mentioned.

So you start a horse in a bosal or a snaffle, not because it is a kinder bit or softer or any nonesense like that, but because by the lateral affect of the action one can ask a horse to release at the atlas, to give, and unlock the spine. That’s why a told Blondmare one always rides with a bend, because that atlas is unlocked one side or the other every step it takes, or you stop worrying about taking steps until it does. It really is that important to unlock the spine. And you can’t pull it out of a horse, hold its head down with devices, or get it with a curb bit.

So you either learn to unlock the atlas correctly and then gymnasticize a horse that has given you control of its spine, or you do to some extent what is being done to horse number 6. Your choice. Learn, or to some extent, make every horse you ever ride, uncomfortable. It won’t be perfect, it won’t always be easy, there are times you will fail. I still fail. But at least I know it and I start over to do it right and change how I do something. This is not about disciplines or believing only one school of horsemanship has all the answers. The answers are with the horse and how its body works. Work with it or against it, those are your choices. Only one of those choices helps your horse.

We can be happy about this horse being ‘flat-shod’, but that’s really about it. Well, and maybe we’re happy about the luxurious mane? This horse has travelled hollow for a very long time. It can’t help it having had its head held up with that leverage bit fully engaged by piano hands through a bent wrist, the rider in an exaggerated chair seat putting his weight back on the horse’s loin. The hand riding has caused the horse to pump the front legs like pistons with no reach – I guess that’s what they want, though it’s detrimental to the horse. That hand ride along with the rider positioning has tightened and dropped the back, blocked the hind legs from coming forward, and prevented any sort of engagement. The result is stringy, piano wire tight muscling, an inflamed sacrum, a thinned and stressed loin, an atrophied back and bulging abdominals. I expect that if we could see this horse without rider and tack, that we’d be looking at a mechanically induced swayback.

Something that’s difficult to see without the image blown up is the landing and takeoff of the hind feet. The left hind is just starting to land, and it’s going to land outside toe and wall. The right hind is twisting as it takes off from the ground, currently pushing off the outside of the toe. This can be a result of foot imbalance, leg crookedness that we’d only be able to see from behind, some other conformation trait such as excessively long tibia, lack of muscular lateral stability (specifically abductors and adductors), or some combination. I believe we can conclude its a combination of some of those with the catalyst being: because the horse is trained and ridden in a way that is detrimental to its health.

The next horse in this segment is neither a gaited horse nor a saddleseat horse. The photo annoys me more than anything. I include it to make a couple of points. One, an itty bitty rider on a big truck of a horse can in fact negatively affect said big truck; the chair seat, rider sitting closer to the loin, and the artificially high held hand on a too short rein – curb fully engaged – causes this horse to hollow and trail the hocks. And it’s a real shame. Though this is not a horse intended for riding, it could be ridden much more correctly, and thusly to the horse’s benefit, without too much difficulty. That’s what annoys me. This isn’t a hard horse to help in the scheme of things. It’s got some really strong conformation traits, like that incredibly short, deep, strong loin, massive hip and deep pants muscling. Two, dressing the horse and yourself up in different attire doesn’t make it so. It might be cute. It might be fun. But have no illusions. If you want to call it ‘cross training’, then do it right – for the benefit of the horse. Yes, I’m thinking about Western Dressage in this moment as well.

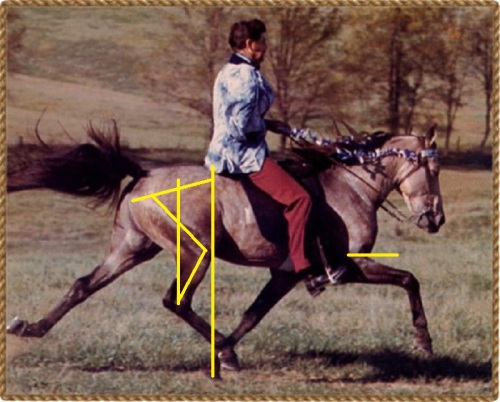

I want to end this summary with an additional photo (8a) I came across after posting the original article and compare it to #2, though we’ve got different angled photos. I love this photo and I’m aggravated by it all at the same time. It’s the right idea, but not quite followed through.

- Again with the leverage bit, even though ridden on a much longer rein. Still it’s caused the horse to get jammed up in the throat and base of neck. The over-development at the base of neck is a clear indication this isn’t a one time only thing. I just want to scream, ‘Get off the face!’.

- Rider in an exaggerated chair seat, sitting on the loin.

Despite those things compare this longer, lower frame gaiting with the more traditional shorter, higher frame gaiting. 8a shows:

- slightly lower knee action – forearm just below parallel compared to forearm just about at parallel for #2

- longer front leg striding – knee reaches to chin and lower leg straight to toe compared to knee behind chin and lower leg curled, and planted front leg is under the horse’s loin compared to planted front leg at mid-body

- not quite as much hind limb articulation for 8a, though the loin is rounder and fuller indicating plenty of loin coiling, muscling in general on 8a is rounder, softer, fuller

- hind stride shorter – hock reaching to mid-pelvis compared to hock reaching to point of hip in #2 and thrusting from a more ideal point

Undoubtedly portions of these differences are conformation related. As an example, 8a is not as proportionately long in the hip, and has a femur longer than tibia vs a femur shorter than tibia for #2 – proving to all those gaited breeders out there that you don’t have to breed in a ridiculously long tibia for a horse to gait. 8a also proves that you don’t have to crank the horse’s head up for the horse to gait, and that doing so will (in all horses) cause the front legs to shorten stride and piston more. I understand that’s desired, but in doing so you reduce range of motion throughout the entire front end, in turn building unhealthy muscle patterns and seizing joints. You also increase the pounding on joints and feet. It’s akin to us taking little steps while lifting our knees abnormally high and stamping our feet.

So 8a doesn’t win a ribbon because the gait isn’t quite even front and back, or there’s not enough knee action, or, or, or, but 8a allowed to lower its frame and stretch its topline like this makes 8a a healthier horse.

Thanks for the great video! It’s really east to see without a saddle how the gaited horse tightens it back and moves it legs.

Are we going to talk about 9 thru whatever down below, or move them up? I put 9 below, but I could talk about more down there or continue up here.

I don’t want to clog up the saddleseat/gaited conversation, but not a lot of people are jumping in. I thought Morganman might stop by to add his outlook as he breeds Morgans, some of whom may go to saddleseat show homes.

Feel free to comment wherever you like. The next set of horses I’ll be doing in a separate article, but if you say more profound things, I’ll just quote you. 🙂

On #8, I’m not seeing the curb as being fully engaged. In fact it looks to me like it is hardly in play. ???

Folliowing this when I can. Really great exercise!

I don’t have anything to say about gaited horses; I’ve only ever seen Icelandics and a Paso Fino briefly doing demo rides at horse events; never ridden one (they are rare around here). All gaited horses look simultaneously amazing and a bit “wrong” to me, so I don’t trust my eye at all.

The poor big lick horse is wearing a bit. The saddest part is they are such a thin twisted wire that you can’t really even see it going into the horse’s mouth. It isn’t a hackamore. 😦

I’ll go against the tide and state that I happen to love the Clyde, sans the rider. He looks happy, reasonably forward, his throat is open, complexus in play and the contact doesn’t look heavy to me. He could track up further and have more weight behind but given his draft conformation, he looks to be relatively free of restraint from the rider. Ideal? No. And why he’s wearing a Lane Fox saddle and full bridle is beyond my conception but I’d consider this horse to be in the middle of the range of properly ridden horses – neither for correct topline development though not physically suffering either. The whole saddleseat thing, pointedly as Mercedes stated having the rider sitting too close to the loin, is kind of silly IMO. Though if she was out having fun on a Sunday afternoon for a few classes, I doublt he suffered much for it. It could be a lot worse. I really like this horse!!

I’m not sure what you’re looking at. Perhaps I need to trace his frame?

He’s hollow, dropped base of neck, hocks trailing out behind…in what world is that ‘middle of the range for properly ridden horses’? There’s no proper about it.

He *could* be ridden middle of the range properly without too much trouble despite being a draft, but he’s not in this picture.

I agree he could be ridden much better, and there is room for improvement, though I’m not as turned off by this picture as many others. “Middle of the range” being not even the same zip code as horse 6, this is painful to look at and really upsets me…..vs one of the more correctly ridden horses, I believe #16 or 17 in your original list; covering ground, tracking well up from behind, acceptance of the bit…..

The Clyde doesn’t appear to be struggling to do his job. He doesn’t have as many variables pulling him apart as the some of the gaited horses. I find him to be ‘typically’ ridden. She isn’t helping him any but I don’t see a horse in pain either. So, yea – middle of the road.

I would say that *we* need to change our view of what’s accepted as middle of the road, because if that particular picture is what constitutes it, then *we’ve* got a big problem.

As long as a horse is moving hollow, its body is being harmed. Neutral, neither helping nor hurting the topline would be what I would want to label as ‘middle of the road’.

This is horse 10, another draft in trot:

Compared to horse 8, which of these two drafts is moving better? And why, what contributes to the better movement?

This horse is also ridden in a leverage bit though with lighter contact, a more open throat, no visible evidence of a bulging lower neck. He’s pushing off from more under his hip than the Clyde, less on his forehand. Back is raised, loin round and full. Both drafts have very laid back shoulders that would fill a collar nicely. I’m not fond of this short and thick of neck, his throatlatch is almost non-existent. It may be perfectly functional but I don’t find it appealing at all.

But I didn’t ask which was prettier, which is somewhat subjective. I would tend to say pretty is as pretty does when it comes to a horse’s movement. This blog is not about like, or beauty contests. It really is pretty much steeped in anatomy, a much more rational approach to analyzing movement.

On that criteria, the second draft is moving better than the first. The first may look flashier or suit some ideal we’ve stored away, but it is not moving well on an objective basis. So if holding the nose in doesn’t create better movement, why is anyone doing it? Why do we even talk about throat latch, tell me anatomically, when and how the throat latch might impede movement?

Maybe some goods would help here:

extended trot, picture slightly tilted but horse is still uphill:

piaffe, note the similarity to saddle seat look, but the superior position of the horse’s spine, no death grip on the curb:

an amateur low level rider, but notice the generosity with the reins, the nose in front of vertical, yet complexus muscle shows, horse is round for the level it is at, close to perfect v’s, not clearly on forehand, relaxation of front leg, no toe flicking here, nice movement, nice balance from rider, this would be helpful to the horse, not breaking it down:

these are three horses at a standstill and three superstar names in western riding, but still illustrative of some points, note the squareness of the horses stance, the alertness but quietness, note the far tight horse, the muscle development, the squareness of the chestbox, the roundness over the haunches of all three horses. The horse in the middle is probably a juvenile, note it is in the bosal, but still standing squarely, the horse on the left is a TB, not the best front legs, but still square and well rounded over haunches, all three have stopped with weight in hindquarter, not the riders position of back and shoulder, one has to be 90 plus, the other pushing 90 and the other 70 plus in that photo, how many of us can sit like that? Notice the draped reins.

The Appy picture is most excellent because not only does it show all the right stuff, but it’s also taken at an angle that allows us to easily see it’s all the right stuff.

The appy is stretching nicely to the bit. It’s an active stretch, my understanding is that the head doesn’t need to go below the level of the withers, but it’s important that the horse be actively stretching out and not just walking around with a low head on a loose rein.

Horses 11, 12 and 13 are kind of a progression from a riding type horse, good bone, a little long in the loin but well muscled with good depth of the loin girth, well proportioned legs with short cannon, a little bit heavy and cresty neck and maybe a head a touch large (or distortion from angle of photograph) with a fairly well balanced rider with acceptable hand placement, and a fairly even trot, not on the forehand, then the next horse, still more riding type, moving fairly balanced, but just constrained enough in the head and neck from downward bearing pressure of rider’s hands to be not quite as good as the 11 horse, and then what I think is an appy with a grey gene and large blanket, who is too downhill to be considered a ‘riding’ horse, poorly ridden by an out of balance rider, too pulled in by the reins with neck and back hollowed, and a trot that almost isn’t. Horses don’t move right if you overly constrain their heads. They hollow so the legs can’t move correctly as the spine controls the kinds of movement you get from the legs, remember the icelandic with his leg folded up and the SI joint discussion. If the rider is out of balance the horse either eventually bounces them off or compensates by leaving a foot under the weight of the rider even if they ought to be moving that foot. Look again at our horses, and look at rider’s tipped way forward or way back and then look at where the horse is leaving a foot on the ground too long, frequently a front foot, but sometimes a back foot, they are holding up their rider to their own detriment because they are kind that way.

I cannot tell you how much I hope some of you are seeing these things and rethinking your own riding. If we help out our horses, they will definitely help us out even more.

Reclining, sitting back or otherwise getting ‘behind’ the horse’s center of gravity will often cause the horse to scoot forward or take off with speed depending on the severity of the imbalance.

Some of us may remember our first riding lessons, when our core lacked strength and we had trouble stabilizing ourselves with it to stay with the horse’s motion, particularly those first times asking the horse to move from walk to trot. The horse thrust us forward with its first step of trot, putting our balance too far forward. In response our horse slowed and went back to a walk. So we tried to anticipate and counter act being thrown forward on the next transition, overcompensating and causing ourselves to be left behind. How did the horse react? Why, it scooted forward and then we either panicked and assumed the fetal position or we tried to correct, over-corrected, and got ahead again, both resulting in the horse slowing and coming back down to the walk.

The video posted by TotallyPeeved illustrates that rider sitting back and leaning back on purpose to illicit speed and then having to use the reins to control that speed. That’s what is happening in several of our gaited photos to various degrees. It’s also what happens in those horrific *suppose to be* extended trot dressage photos. But photo #2 illustrates that a rider can remain significantly better positioned and still get gaits, speed and control without hanging on the horse’s mouth. The simple act of ‘sitting up’ will slow a horse in the same way the simple act of ‘sitting in’ will speed them up. Sometimes a riding situation calls for ‘shouting’, most times a ‘whisper’ will do.

Hey Mercedes, do you know of a good place (here?) to get riding critiques – I’m getting back into it after 15 years away from regular riding, and would really love to get some GOOD eyes on my position etc, whether it is helping or hindering the horse and what I should be working on 🙂 Then I can go back and tell my ‘instructor’ (yeah, right – I’m basically using her and her dead quiet horses to get my feel back and then will just go do my own thing) what specific things I want to work on.

With all the fab information I’m learning here I’m getting a good basis on how to look at the horse conformation wise and what training could help improve him, but no real idea if what I’m doing in the saddle is actually helping all that much. I certainly don’t want to be riding if it’s not achieving my goal of helping the horse to get better, or at the very least not get worse, each time I’m on it’s back – what’s the point otherwise?

I think (hope / pray) I have a good basic position, and know most of my worst habits (and am trying hard to un-learn them before they get re-set this time round ), but I also know I’ve got loads of little ones that are preventing me from really being able to help the horse, and so far my ‘instructor’ isn’t picking them up. Sadly I don’t know any other people around here that are any better, either.

Thanks,

Kahurangi

New Zealand

If you want to be a guinea pig, you can send me pictures (and video) of yourself and I can post in a blog article. You’ll get lots of various input that way. Otherwise I can do it privately, but it’ll cost you. 🙂 E-mail the blog: thehoovesblog@gmail.com

Horses 14-17, again, all at a trot. First what looks to be a Freisian, a horse that tends to be built level, but also tending to be a high resting tonus horse, ie, always “on” much like arabs, one generally needs to teach these guys to relax and stretch else their gaits become too sewing machine like. Also known for carriage work, and flashy appearance at that, they tend to have legs more like gaited horses, ie, longer cannon to increase the appearance of the action, and a laid back shoulder. This trot is fairly level and even.

The littler black horse, maybe some stock blood, is more down hill, not quite as even or big a trot as it is capable of, but somewhat inhibited by puppy dog hands and someone that probably stands to rise at the trot creating uneven contact as the hands rise at the posting trot. This horse is not particularly engaged, and even with a longer rein its moving with its nose poked out and no lift to the base of the neck. Rider committing a cardinal sin, looking down, giving the horse no direction.

The next two are hunters, the first showing a fairly decent trot, not perfect but good, but also not using its neck well, but both horse and rider seem to be looking at something so the head could have been raised to see something out towards the horizon. The second, a little bit more relaxed looking, pretty good trot, but notice hind stepping further inside to avoid the front foot, I don’t think the rider is asking for lateral movement, the body isn’t set up that way, so I think this horse is doing its best to give a big trot, but also not step on itself by going crooked.

Here is another place to play, all of these horses are moving fairly forward, but which ones seem to be most ‘with’ their riders as to where to go and how to get there? And what part of the horse’s body is telling us what they are thinking of doing and paying attention to?

just a short comment on the iceys and the high knee action (e.g. the 8a vs horse 2 comparison). from what I understand, the iceys have been bred for higher than ‘typical’ action so that they can go fast over really nasty terrain. altho having said that, there has been a tendency in recent years to breed for more ‘flashy’ movement that what would be strictly necessary. some controversy exists as to whether the horses with massively high action last as long or not.

Nobody in their right mind – considerate of the horse – goes speed over really nasty terrain. There’s a reason racetracks are groomed surfaces.

Having raced Standardbreds of various ‘action’ I’ve not found any correlation to soundness. though that doesn’t mean one doesn’t exist. There are so many factors once a horse starts travelling at speed that the ability to isolate just the horse’s action and determine if it plays a significant role in soundness is pretty much impossible.

Certainly it (action) can change the timing of the footfalls. And certainly the more action the horse has the more energy it expends at speed.

horse number 1, the grey icey, is pacing. those little stinkers can get upwards of 30mph at that gait. on the track, the acceleration can kind of blow the riders off the back of the saddle. so yeah, the guy is sitting to the back and has a collapsed core – but that may not be the way that he would look at a slower gait.

Standardbreds have been ridden (and still are in some place, if just for exhibition) and the riders don’t sit on the back of the saddles like that. Those horses also can reach 30mph. Riders of TBs also don’t sit in the backs of their saddles at speed. We also have pictures 2 and 3 to show that a rider can sit in a more balanced position at speed.

I’ve been thinking about how hind legs move over the past little while (since I had an ahah! moment in an earlier thread here). Yesterday I was lurking around a dressage chat forum where “competitive” and “classical” riders were taking pot-shots at each other. I read on because I was interested to see how the “competitive” riders justified what they were doing not because I was actually learning much :). At one point, someone posted old film or video of “classical” past masters, where the horses had more correctly loaded hocks in collected work. The response from at least one of the “competitive” riders was that the rear legs of the classical horses looked stiff and locked, not loose and articulating like the rear legs of modern dressage horses.

That was interesting, because it means that people are seeing the popping hind end, caused by trailing behind and being on the forehand in piaffe and passage, as a positive and desirable thing. True collection looks slow, fixed, “weird,” because no one is used to seeing it. I also found it odd how many “competitive” riders in that forum said (defensively) that they never saw a horse being ridding behind the vertical, in training or in competition. I’m not sure what they think btv means: maybe they think it only means extreme rolkur? Maybe they just can’t *see* btv? It is true that if every horse you see is broken behind the poll, any horse going correctly (even if it is on the vertical) looks a lot less “round” and “finished.”

So I think part of the debate is that most “competitive” riders would subscribe on paper to the old rules of dressage, but they get taught to do, to feel, to see, and to value, something very different while being told that it is in fact consistent with the old rules.

It’s a little bit what happens with images of women. Every magazine, website, make-up book, mother, acting coach, etc etc will praise “natural beauty.” Almost nobody would go on record defending “totally artificial beauty.” But then we are fed so many images of girls and women in full make-up, photo-shopped, etc., that we almost never see an image of an actual unpainted woman, unless she’s just been pulled from a flood or fire in the middle of the night. And so we have no concept of what “natural beauty” might be. “Stars without makeup!” is a shock horror scandal feature of supermarket checkout magazines 🙂 probably worse now than just being caught going commando. Anyhow, that’s a separate rant, but I just meant that there can be words that everyone would say they agree with, but what they have been taught to see and value and do is totally different.

Thanks for this great post, Paint Mare. *We’re* facing a serious dilemma in the equine world, having lost most of the truly knowledgeable horsemen/classicists. Virtually nobody knows that what they’re looking at is not correct. Of course the hind legs are going to look stiff and locked in a truly collected horse compared to the pogo-like ‘legs-everywhere’ of a hollow, leg-moving non-collected horse. And when there just aren’t any examples available of correct, anywhere, then correct is going to look wrong. I can only hope that we’ll return to correctness via the same circle that such things as fashion are on – though a much bigger circle.

On a side note for everyone: I’m now pretty much training horses full time and just haven’t had the time (or energy) to get to the next summary article.

jrga: I am here, but keeping quiet. Very interesting conversation.

Interesting that number two is in a big old curb bit, just not the type we usually see. Search for icelandic horse bits and you will find it quickly.

Just a comment on #7. If this horse isn’t gaited I would be shocked. He has the classic look to his structure that we see in the gaited Morgan’s, and rocky mountain horses. Tend to be on the smaller side with short strong backs and wide shoulders.