In the last article (To Plow Or Not To Plow) I talked about horsepower, where it comes from structurally, what bone ratios are needed to get the power ‘forward’, what kind of build allows for ‘4-wheeling into the ground’, and what type of a loin can survive it. Now we switch ‘gears’ and look at where speed comes from and why it can be deadly.

Speed requires certain conformation traits, just as power does, to be achieved. It starts its generation from power. We can assume, then, that we have to start with some of the same conformation traits of that big plow horse.

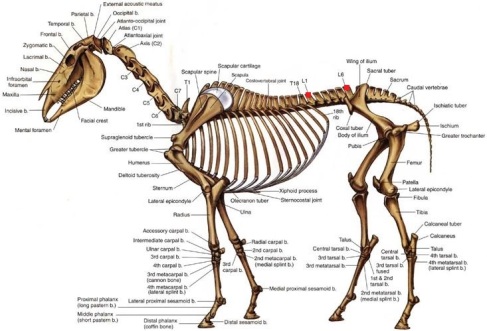

1) A well-placed lumbo-sacral joint (created between the last lumbar vertebra (L6) and the first sacral vertebra (S1) that the entire hindquarter pivots on). The LS joint needs to be located at, or in front of, the point of hip to get the full benefit of;

2) Good length of pelvis, at least 33% of the entire body length, however, if you want to get serious about horsepower (and therefore speed) that number should be upward of 35% or more.

3) Proper angulation of the hind leg. Over angulation of the hind leg (a leg mathematically too long for the body) puts the brakes on speed. Its stroke is too long, too slow; it can’t get fully under the body to power a horse forward. It’s also prone to injuries like curbs and bog spavins, and is often accompanied by cow hocks or bow-leggedness. The latter two create torque that ratchets up exponentially with speed. And while a post-legged hind leg (a leg mathematically too short for the body) lends itself to quick strokes and thrusting with power, it’s also undesirable as it places too much stress on the stifle and hock with their wide open, and therefore unprotected, joints. Sticking stifles and arthritic hocks are often occurrences. Having said all that, the angulation of a ‘speedy’ leg will be ‘straighter’ – but still fall within the acceptable range of ‘proper angulation’ – than that of the slower dressage or gaited horse hind leg.

4) A loin no greater than medium in length, so that all the power generated by the haunch can be transferred forward without blowing up the loin. Short is just as okay here as it is in the draft horse. The loin is a freespan (has no ribs to support and add strength), therefore length is its enemy. Strength in this area is of greatest importance, especially if the horse has great pelvic length, which it must have to be fast. We also need broadness across the loin and depth. (Note: A racing fit horse will appear shallower through the loin. This does not necessarily reflect inherent weakness of the loin. Whereas a shallow loin on a non-racing fit horse, a riding horse or a draft horse is immediate cause for concern.)

5) Either a square build or a ‘proper’ rectangular build. A square built horse is compact front to back and stands low to the ground; height and length of the body are the same. A ‘proper’ rectangular build is a slightly longer body, where the horse stands over more ground, but doesn’t stand over a lot of air. This horse also remains relatively low to the ground. Good racehorses tend towards the ‘proper’ rectangular build, especially horses that go distance. The leggier the horse, the more energy is wasted swinging the legs the length of their stride and the more easily things can break. Consider how much easier it is to break a one inch thick, two foot long stick over your knee, versus a one inch thick, one foot long stick.

While some traits remain consistent, others change and the degree of difference varies. We want third gear for speed, not just the powerful, but slow first gear. So now that we have power potential from the above traits, how do we keep it, get top gear, and more importantly keep the horse sound?

5) Hocks and stifles set higher; that is stifles that are clearly above the height of the elbow, and hocks that are clearly higher than the knees. The height of hocks and stifles is determined by bone lengths in the hind limb, and the ratio of those bones to each other plays the role of determining ‘gear ratio’. In a racehorse we expect to see the tibia exceeding the length of the femur. That’s exactly the opposite of what we require for the draft horse (and for the riding horse).

6) Substance. Big, clean joints. Bone thickness is typically less for a racehorse, than for a riding or draft horse. This is a compromise we’ve allowed over the years mainly because racehorses perform on level, manicured surfaces, and the less weight having to be carried over the distance, means less energy required to do it, which in turn means faster times over distance. However, it’s not a ‘requirement’ that a racehorse possess less bone; meaning a racehorse can possess greater bone thickness and still be fast. There does remain a ‘minimum’ bone requirement for racehorses, which is 6” per 1000lbs; a full inch less than for all other horses. Think about that and keep it in mind for later. Here I’ll include feet. They should be of an appropriate size, shape and construction. Foot faults can be disastrous in any horse, but in a racehorse they are a red flashing neon sign.

7) Appropriate muscle mass and type. Sprinters should display larger amounts of the big, bulky, fast twitch muscles, while horses that run distances of greater than two miles will possess significantly more lean, slow twitch muscling (think Arabian muscling versus QH muscling). The middle distance runner possesses a balance of both. Soft tissue attachments should be clean and smooth regardless of type.

8) Downhill Build – usually and mostly. A more level build can be seen in gaited racehorses and sometimes in distance runners.

9) Not Too Much Limb Action – This references mostly the front legs. The more joint articulation (ie., knee action) a racehorse has the faster that entire leg has to be to complete the stroke compared to a less articulating jointed leg, AND the more energy burned trying to do it and maintain it. That means a ‘fancier’ moving racehorse must possess more stamina to maintain speed than the more efficient less fancy mover. It also tends to mean that a ‘fancier’ moving racehorse requires more distance to get up to speed and you are likely to find this kind of mover coming from off the pace, rather than setting it. (Note: An exception to that would be trotters, who require more front leg joint articulation to remain interference free and time the trot at high speed.)

We now have the basic build of a horse designed for speed. Let’s look at a few of the great ‘speedsters’; TB – Secretariat, QH – Dash For Cash, Standardbred (pacer) – Niatross

They look remarkably similar. And yet, there are distinct differences as expected. Three different breeds, one gaited, but all essentially sprinters.

Though Secretariat raced the furthest distance of the three (Belmont, Rothman’s International (that one on turf) at a distance of 1 ½ miles), he showed tremendous bursts of speed that he maintained over distance. His advantage was three-fold; rateability, extraordinary joint flexibility, and stamina (that extra-large heart). His heart was never weighed during the necropsy, but it’s widely considered a fact that Secretariat possessed a heart of extraordinary size. Adding his sprinter type speed to those factors, and we have track records set by him in all three Triple Crown Races that still stand four decades later. He went 16-3-1 in 21 lifetime starts. He’s known today as a broodmare sire.

Dash For Cash is the second all-time money earner for QH racehorses with over $500,000 followed only by his son First Down Dash. That’s saying something since he did it almost forty years ago. He won 21 of his 25 lifetime starts and had three 2nd place finishes. He’s the leading broodmare sire and you’d be hard pressed to find a top money earning running QH that doesn’t have him in his pedigree.

Niatross won 37 of his 39 races, thirteen of those as a two year old. He finished 4th in an elimination round of The Meadowland’s Pace after breaking stride and in is only other loss he spooked during the race and fell over the guard rail. He was the first Standardbred to break the 1:50 barrier with a 1:49.1 record that stood for many years and retired the richest earner in history at the time.

Not to forget about the popular European racing sport of Steeplechase: the great Desert Orchid.

Desert Orchid raced an astonishing 70 times and finished with a record of 34-11-8. He had an attacking front end style of racing and is considered by many to be the greatest in that category, as well as the greatest jumper. One conformation trait to note is the height of his knees. A lower position created by a short cannon bone and longer forearm is desirable for jumping. (Actually, it’s desirable for most disciplines.) Secretariat’s knee is the next lowest of the bunch, so it’s not surprising that he’s been known to throw some individuals with jumping form.

Racehorses have enjoyed the attention of the scientific and veterinary communities and undergone hundreds and hundreds of tests and evaluations, all with the intention of understanding the rigors placed on them, and with the hopes of being able to decrease the likelihood of breakdowns. There is no discipline more demanding of the horse’s entire body than that of racing.

Standardbreds are unique in the racing world in that they rarely have catastrophic breakdowns on the track. I’ve followed the sport closely for three decades, and watched thousands of races from grass roots level to top stakes competition. I’ve never seen a single Standardbred have a catastrophic breakdown on the track. I’ve seen a few dozen fall down, and three collapse in races from heart attacks. This is not to say they don’t ever hurt themselves on the track, because they do, but rarely is it catastrophic – unlike Thoroughbreds. I can’t comment so much to Quarter Horses as my exposure to them is far more limited, but of the few hundred QH races I’ve seen, nothing catastrophic has happened.

So why is that? There are a few reasons;

1) Standardbreds race at speeds of 10%-15% slower. As speed increases so does the pounds per square inch of pressure placed on soft tissue, joints and feet. I couldn’t find a study from which to quote figures, but I did find the following study of four QH’s. It’s a lot of numbers and technical jargon, but if you can muddle your way through, it’s fascinating. http://www.iceep.org/pdf/iceep2/_1129105705_001.pdf What was most striking to me wasn’t the amount of pressure the legs and feet sustained (I already expected that to be high), but how that pressure varied on each foot of the stride and how the amount of pressure changed depending if the horse was on the straight versus on the turn, as well the noted change of pressure when the horse switched leads and how it differed from the other lead.

2) Standardbreds get to divide the pressure placed on their legs and feet, since both trotting and pacing see two feet hitting the ground at (almost) the same time. (The hind feet actually touch a fraction before the front.) While a galloping horse must support all the weight and pressure on one foot at a time.

3) Standardbreds tend to carry more bone, often exceeding the required minimum of a riding horse of 7” per 1000lbs. Circumference matters. You don’t put a big building on skinny pillars, unless you want to have a problem. I can see the hands going up – but, but – what about bone density? Here’s the deal, dense bone is great but dense bone can be brittle. Circumference matters. The pillar doesn’t have to be as dense to support the structure if it has circumference.

Here’s a picture of the famous Ruffian. Many consider her as a candidate for the greatest racehorse of all time.

Upon close examination, Ruffian possessed every conformation trait required to be fast, but she lacked the one that probably would have saved her: Substance. It’s clear at 17h that her joints weren’t big enough, and that she didn’t possess the minimum requirement of 6” per 1000lbs.

Her sire, Reviewer, broke down three times on the racetrack and his fourth breakdown, which led to his euthanasia, happened in his paddock. Her dam, Shenanigans, broke two legs during her lifetime and was later euthanized after colic surgery. Shenanigans sire, Native Dancer, is rumored to be the one responsible for a ‘soft’ bone issue in his offspring, but frankly, I don’t buy it. But if it is true, why does he show up so often and so much in the pedigree of many of today’s Thoroughbreds, almost four decades after Ruffian’s demise? Why would TB breeders purposely take the chance of passing on genetically weak bone from generation to generation? What good is a fast horse that can’t stay sound? Because one out of a thousand might be able to?

Here’s Native Dancer. He certainly had substance.

I was unable to find a picture of Reviewer or Shenanigans to see how much bone those horses carried. But I did find a photo of Bold Ruler, the sire of Reviewer. Hmm…it might be my eyes, but I see a striking resemblance between him and Ruffian.

So here I am, still on the substance bandwagon. Let me explain why it’s so darn important.

The front legs of the horse are designed to act as pillars, whereas the hind legs act as springs. As with any foundation column, straightness, size and integrity determine whether the building it supports stands for all eternity, begins to lean under its own weight, or collapses. The same is true of the horse with an additional caveat; the horse is not a static structure, but a moving one. Consider the greater importance of the foundation of a skyscraper that sways in a stiff breeze versus a one-story home the doesn’t budge under the same windy assault. Not only must we consider moving weight above, but now torque comes into the equation. Therefore, the horse’s front legs need to be straight, possess enough substance (circumference) to support the weight above and be free of fault. Those requirements become even more important when we consider the following:

To be fast, a racehorse MUST perform on its forehand. Go back to the QH study I linked and see that the front legs always carried a greater burden. Racing is biomechanically opposite to that of correct riding. Dressage is the antithesis of racing, with the horse transferring weight to the haunch, rounding the back, lifting the withers, raising the base of neck, dropping the head from the poll and coming onto the vertical, while increasing the depth and center body step of the hind leg and decreasing the stroke speed. The Dressage horse’s body compresses, impulsion shifts forward energy into upward energy and the horse carries itself on its haunch high off the ground, propelled by hind legs that coil and uncoil like springs. The racehorse transfers weight to the front legs, hollows its back, drops its withers, drops its base of neck, drops its poll and sticks its nose out, while the stroke of the hind leg thrusts with quick, shorter (relative) strokes. Impulsion is all forward energy, the horse pushing itself forward with the coiling and uncoiling of the hind legs and pulling itself forward with its forelegs, as it lengthens its body and lowers it to the ground.

To be fair, bone alone isn’t enough. There are other factors besides a lack of substance that can lead to catastrophic breakdowns;

Poor foot balance and bad shoeing choices. Under those pillar-legs are feet. Any deviation from correctness has an exponential disaster rate under the pressure of speed. No human sprinter or distance runner would think to run in shoes that put undue stress on their knees, ankles or feet, and yet… Here’s a study of how different shoes increase or decrease the likelihood of breakdowns. This one addresses toe grabs on shoes, something you see in all the racing breeds. http://www.thoroughbredtimes.com/horse-health/1997/march/29/a-potentially-dangerous-step.aspx

Bad training and conditioning. It’s widely understood that the reason racehorses are started at such young ages is to begin bone remodelling. But that has to be done slowly and carefully over a long period of time. Push a horse too fast, too soon, and the horse ‘bucks its shins’ (micro fractures of the cannon bone). Push beyond that and you can bet on a disaster. Note: I’ve only ever seen one Standardbred suffer from bucked shins and that was a big (17h) two-year old trotter that I will plainly say was being trained by an ultra-idiot, but I’ve seen lots of Thoroughbreds succumb. Is that because Standardbred trainers are generally better conditioners of horses, or perhaps because Standardbreds carry more bone in general and are less susceptible?

Some ‘other’ sort of conformation fault. This could be a benched knee, a too long pastern such that when the horse gets up to speed it starts smacking its sesamoids on the racetrack. Cow-hock, bowleggedness, deviated cannon bone, rotated pastern, flat soled feet. Pick your poison; some work faster than others, but the end result is always the same.

A problem with soft tissue. Suspensory ligaments can tear, tendons can rupture. This can be related to conformation faults, like that too long pastern. It can also happen because of poor foot balance or bad shoeing choices. And it certainly can happen with improper training and conditioning techniques. It can also be because of;

Accidents: A racehorse can take a bad step. They can hyperextend a limb. They can get jostled in a race, lose their balance, fall down. They can stumble coming out of the starting gate. But that’s not what happened to Ruffian. She was galloping along just fine in her match race against Foolish Pleasure. She didn’t have a race accident like Niatross pictured below.

Here’s the video of Niatross’s fall if you’re a sucker for having your heart in your throat: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LpUSssOlKEg

And if you want to break your heart, here’s the video of Ruffian’s last race: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YnZFnCvKspw

I say one more time: Speed Kills. So if you want to play the game, including playing it on your barrel horse, on your eventing horse, on your speed round jumper horse, or even on your endurance horse, where besides speed you’ve also added torque and sometimes uneven terrain, do the horse a favor and pick one suited to not only the task but one most likely to stay sound doing it. And then, train, ride, and compete with consideration and caution. This is a living, breathing animal, not a machine.

My final thought, perhaps unpopular: The demise of Ruffian had an upside; she could not pass on her small-jointed, spindly stick-legs.