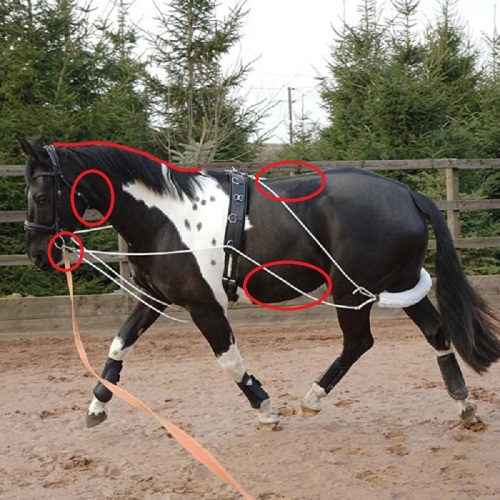

Longeing is an excellent way to improve our horse’s topline. Without the burden of the rider, the horse can more easily find a rhythmic, relaxed and balanced way of going. The circle naturally encourages a deeper, more center bodied step from the inside hind, triggering the cyclic action of the ring of muscles. This, of course, still relies on the skills of the person doing the longeing. Letting a horse race around on the end of the line braced in counter bend, leaning on a shoulder, and escaping out the haunch is useless to the horse and does damage. Picture #46 shows an effort towards correctness.

Unfortunately, the effort is not entirely successful. I’m making the assumption that the person at the end of the line is in the process of fixing this horse, rather than ruining it. I could be wrong, but it’s the impression I get. The horse’s tail is held in that lifted, but relaxed position we like to see with no apparent swishing, there’s suspension to the gait, the inside ear is on the handler, the eye soft, the line giving. And while the sidelines are a bit of hindrance, they aren’t the reason the horse doesn’t get to the desired result.

The horse is taking a good step behind, reaching forward to the back of the saddle. A great step would be under the weight of the rider. This horse has plenty of potential to take a better step with a decent hip length and a very good femur to tibia ratio (nearly identical). It’s a riding conformed hind leg.

We can clearly see an abdominal line indicating the horse is using them. The biggest hindrance for the horse is the injury to the loin. There is a noticeable hollow in the loin with very tight, angular muscling. This shouldn’t be, and it’s quite likely that if we could see this horse without the saddle, that topline tightness and angularity would continue all the way to the withers.

Moving to the front end we can clearly see the tubular complexus muscle engaged and working. The problem is that it’s uneven. The muscle is very evident in the first third of the neck and then begins to fade until it disappears well before the shoulder. That muscle should be equally engaged the entire length of the neck and right to the shoulder. The crest of the neck also shows this irregular usage with flatness starting at the poll, then some arching that peaks just beyond the throat line, to then flattening, and finally dipping a bit just before the withers. The latter half of the crest also thins.

The horse’s throat is closed, and the horse is behind the vertical evading the contact of the side reins. Yes, even though they are loose. This added to the loin issues causes the horse’s shoulder to be blocked, and the horse to take a shortened step with the foreleg. Essentially this horse is compressed from the back and the front. Contrary to popular belief, this is not collection.

Picture #47 reflects all that is wrong with the industry’s knowledge base. You can not tie, pull or hold a horse into collection and this horse shows it.

This horse has a fabulous hind end. Big hip, femur clearly longer than tibia, breadth and depth of loin. There’s power and potential galore, and absolutely no need for this contraption. If the haunch was lacking, this horse would be physcially suffering far more than it is.

It’s easiest to see what’s gone wrong by looking at the horse’s front end. Throat is closed. (Hard to see on a dark colored horse like this, but if you enlarge the photo you can see what we’d call on a person, a double chin. The crest of the horse’s neck forms a wave, flat behind the poll, then arched, then dipping before the withers. There’s no evidence of complexus muscle, which there should be with the horse stepping as deeply from behind. There’s also no evidence of abdominal contraction. The back and loin are showing tightness.

A final point is the longe line attached to the inside bit ring. This would be equivalent to a rider riding on the inside rein, which is exactly not how we ride, especially not a circle.

The pony represents the most engaged (and correct) trot of the group, and therefore the one stretching and improving its topline the most. It has nothing to do with the handler and everything to do with the dog.

Lots of hind limb joint articulation. Even, full arching, and reaching of the neck. Slightly ahead of the vertical with an open throat. Wither and back lifted. A taller dog might produce a higher carriage. 🙂

It’s a shame we don’t get to see horse #49 without its clothing. I’m unsure of the purpose of putting boots and a bridle on a horse to longe it, but leaving the blanket on. If there’s a concern for the horse catching a chill (if it’s clipped and it’s a cold day), leaving the blanket on while being worked risks over heating the horse. Maybe someone else can come up with a plausible explanation.

Despite the blanket being on, we can still glean some information. This horse is just moseying along and yet he? is taking a bigger stride behind. Is he just that well conformed behind? While the blanket may be restricting shoulder movement a bit, we can see that the main culprit is a short humerus that barely makes 50% the length of the scapula.

Secondarily, the neck shows poor development even while looking well-structured. I’ve circled an obvious lump in the neck that shouldn’t be there, and I suspect the vertebrae are jammed.

In terms of topline development: Neutral. If your horse moves like this on line, you’re not doing anything good or bad to its topline.

(My apologies for not being around of late. Busy training horses and the last thing I feel like doing at the end of the day, when I’m tired and warn out, is doing more horse related things. This is a fine time (and I’d welcome it!) for anyone interested in writing an article for the blog to submit it at thehoovesblog@gmail.com.)

I don’t know, flies maybe? Could that be a fly sheet? Anyway, love the easy to follow critiques, and for me, they have to be easy. I have learned so much from this blog, I realized that my horse was evading me a bit, even though we just poke along on the trail, and I have switched from my mechanical hackamore back to a snaffle for a few months. I really think he has improved his topline just a bit, which is pretty good for us. Thanks!

Welcome back!

Longing to improve how the horse goes is actually quite a skill. My coach can get the horse moving its haunches out, stretching and stepping under, in just a rope halter. I still find it hard to influence the haunches once the horse is out on a 20 meter circle, though I can get a shoulder in or shoulder fore on a smaller volte, where the horse still responds to my pressure on her haunches. I’ve traded up to a lightweight lunging cavesson that tilts the head inwards, since the rope halter encourages the head to tilt outwards.

Once the horse got going more balanced under saddle, she’s been more likely to move more balanced on the longe and even at liberty.

I’m in a strict no side-reins program, but I see a lot of wrong-headed things being done by people who do use side-reins to get a “frame,” which, once they are riding, has to be maintained by replicating the side-reins, that is dropping hands below the withers and sawing on the bit. I will concede that there might, some place and somewhere, be a “use” for side-reins, but I have never seen it, and I can’t think of anything you’d use them for that couldn’t be better accomplished in other ways. I don’t quite see why you’d want to the horse to learn either to lean on the bit, or to stay just behind the bit, which are the two options, it seems to me, when the bit is fixed and not being held in a careful, following hand.

I’ve used side reins for two different situations, neither had anything to do with setting the horse’s head or wanting the horse in a ‘frame’ – so entirely unconventional reasons.

The moral of the story is that we aren’t as interesting to our horses as a dog. *G*

The mental side of the work we present to our horses is something we overlook. If we are boring our horses to death, they aren’t likely to find the mental and physical energy to offer us engagement. Longing for that reason is dangerous and one must be prepared to keep it short and sweet. All of our work should use the lesson plan, terrain, obstacles, other animals or people to add a spark of interest to the work.

I think I might have mentioned that one of my guys loves to cross the teeter totter, you don’t have to ask for much, just point him at it, he lifts, gets livelier in his movement, he’s off to do the teeter totter. He likes taking a walk down the road to visit the neighboring horses and cows. He’s up and alert, not spooky, just forward and ‘on’ in a way he generally isn’t if he’s doing circles in the arena. We need to learn to project that excitement and energy into more types of work and pick things the horse can understand as ‘work’ instead of drilling the same movement ad nauseum. Horses who are glad to be doing what they are doing are going to do more to straighten themselves and help us help them than horses who have had the life ridden out of them. If you’re not having fun, your horse probably (almost certainly) isn’t either.

I have been trying to compose a response, and all I can come up with is exactly what you have said.

I think that I can put this this way. When you train dogs, you need to establish the dog’s willingness to work, or you are going to have an unenthusiastic dog. With dogs of course, this is easier than with a horse. Since I trail ride, it has been easy for me to get that willingness. If the horse is nervous I can keep to well known trails. They get bored, I can go off on new trails. I can usually find a clump of grass for a snack before we head back.

LOVE YOUR ARTICLE MERCEDES! a friend just sent it to me …… I have been studying with Jonathan Field for about 16 years and we use the long line to play with our horses we can offer then the “shape circle” no side reins are used and the line is attached to a rope halter. We use the line as a “rein” and our stick as our “leg’, to “help” our horse shape themselves, they learn to “carry” themselves on their own and will build muscle without tension, as there is nothing to “hold” them in place but their own mind. … I guess that is assuming that the human doesn’t ask too much too fast or for too long! LOL Often I will ask my horse to shape up, then let the line out long and let him go loose, then maybe shape again … etc…. As horses get fitter and understand what is asked of them, they will usually start to offer vertical flexion and engagement on their own! The “shaping circle” is wonderful to strengthen younger horses, all the muscles, tendons and ligaments and also building the back muscles up even before a horse carries a rider, great for keeping older horses top line …. the longissimuss dorsaii , just to mention one of the muscles they use ! (sorry can’t remember my latin spelling) If I see a horse (could be old or young) carrying the haunches or shoulders in too much on the circle I can use the stick by pushing it towards the body part to remind the horse to not lean in, it’s great for helping older horses who have gotten into the habit of leaning in. Laura 🙂

Some thoughts on conformation and topline. Yesterday I went to watch friends of friends schooling up to five feet jumpers, competition-ready horses. This is the first time I’ve been “back stage” watching horses and riders of this caliber (as opposed to up in the grandstand). The horses all had high-set on necks, relatively sloping shoulders, long and steep humerus, and tight angles between femur and pelvis (one horse had a more open angle and he was not as happy jumping). I now see why people prize warmbloods, and also that most of the warmbloods I’ve seen up to now are a bit funky looking, even if they usually have a nice trot (as a kid, I was around fugly grade horses, and as an adult, around the lower end of “nice”).

I was happy to see that the riding was thoughtful and sensible, and people stayed calm through refusals, and eventually got the jump. The only thing that struck me was the topline of the horses once the saddles came off and the horses relaxed. They tended to have big hollows behind the withers, and the back muscles looked a bit flat and locked down. No-one had a hunter’s bump but there were a couple with a bit of roughness further back on the croup. The horses were a good healthy 5 body score, and clearly fit. But the topline suggests to me that they could be doing more in flatwork, I think. Would the trainers just think this wasn’t necessary?

I realize that competition dressage training wouldn’t fix this problem, and would in fact create new problems, which presumably the trainers would already have figured out, so maybe they don’t have techniques for this? You’d think though at that level, they’d have figured it out?.

*snork* Rarely anyone (in any industry) figures it out, even at the highest levels. I don’t know what else to tell you.

No, from what I’ve seen not enough ‘correct’ flatwork is done. I’d bet my own money that most of the horses you saw are longed in side reins and ridden flat in draw reins.

Absent an injury, which ought to be treated and healed and the horse returned to work when well so it can rebuild the topline, if the horse’s top line says it isn’t well ridden, it isn’t well ridden. We don’t need to ‘see’ it ridden, its body tells the truth. A horse can be ridden kindly in the sense of no violence or malice toward the horse but not correctly to build itself up, which is an unkindness in its own way. But it is really hard to learn to ride correctly in the sense of helping a horse compared to riding to a sport standard. People want to win, fewer people want to take the time to learn to help their horse and make that a priority over winning or doing the recreational riding of their choice the way they learned it.

Isn’t the saddle a cause of this problem?

Yes! … aside from poor riding, .. saddle fit can be a major cause of problem for lack of muscle when the saddle is pinching, putting pressure on muscles, withers, spinus process, etc… which will cause atrophy of muscles, and even lameness. (Won’t get into conformation… that’s another topic, you can still work at keeping a horse with bad conformation sound and happy, and have a good top line, it does take a lot more work to do so! Nowdays more riders are becoming aware of proper saddle fit, especially since it may mean the difference of winning the class or just placing …. I know that money shouldn’t be the reason for the change … however I am glad to see more people taking an interest in how their saddles fit. There are a number of great videos for western and english saddle fit, free for anyone … that has access to a computer! We have wonderful saddle makers all over the world building saddles to keep our horses happy. Most of us have invested a lot of money, time, as well as our heart and soul for these wonderful animals that share our lives. Investing in well made, well fitting saddle is something we can do for them, to keep them sound and happy thru out their lives. I have custom made english and western saddles and both my horse and “I” love them….. they were well worth the price and if you amortize that over many years, it’s not so bad! LOL

Watching nice, competition-ready warmbloods, the issue is probably not as much saddle fit (use of a saddle fitter is standard operating procedure for this set) as what Mercedes/ JRGA point out: the horses are simply not ridden well on the flat. I think you’d find if you spoke to these riders, they would in fact say that they believe good flatwork basics are important for jumping and that they school on the flat regularly. But they don’t have the skill and expertise required to truly improve their horses by flat riding. They’re almost certainly putting the time in (hence the fitness level observed) but lacking the ability to get a better result from that time. And probably most of these riders are focusing on their assisted time (ie with trainer, in clinics) on jumping and are muddling through the flatwork on their own, probably out of the belief the flatwork is the easier part.

Step down a notch in terms of how much people spend on their horse habit and then I think you very much add saddle fit on top of the lack of riding skill to the problem. The next step down on the money ladder acknowledges saddle fit as an issue, but thinks “my trainer looked at the saddle and it seems fine” is sufficient answer.

I agree that saddle fit can be part of the problem, a too tight saddle deprives the horse’s muscles over the back of room to function, expand and contract, helping to pull in blood and expel it with waste matter, so the muscle is improved. It can also cause the rider to hit the back beyond the vertebra supported by ribs, greatly increasing the chances of causing damage in the lumbar region. A saddle that pinches, bridges or hurts in any way may cause the horse to sink in the back and defeat building a top line.

But so too does riding the horse hollow or pulled behind the bit or in a martingale or side reins as they push out against the bit, drop the base of the neck, etc., hollow the back and trail the hocks, so the back is damaged rather than helped by building correct muscling to protect it.

Don’t get me started on saddles….but I need to just point out that the “neutral ” pic is not necessarily neutral if the horse doesn’t normally travel like that. Its a lot of work to get my mare to travel in that “neutral” position under saddle or lunging. And when she does, even part of the time, it makes a huge difference for her. Its day and night. Of course it is not the end goal. But on our way to better carriage we get ” neutral more and more and for us that is huge.

I would agree that at the level I was watching, saddle fit is not going to be the issue. I don’t know if these horses are lunged in sidereins or ridden in drawreins. I’ve seen the results of sidereins and riding overbent at my own barn with the low-level “dressage” wannabes, and it puts a characteristic lump up by the poll that I didn’t see on these jumpers. My guess is they don’t do much besides jumping and “jump warmup” would be cantering around until the horse got focused a bit. I do appreciate that in jumping, if its going well, you get to let the horse have its natural head set, looking up alert at the jumps. But that natural headset doesn’t produce any stretch or lengthening. These horses were too well built to ever look “inverted,” but I suspect that functionally, they were a bit at times.

There should be plenty of stretching and seeking contact in jumping despite a ‘natural head set’ because it’s part of engagement, which is a requirement of jumping with bascule.

Yes, but when does one ever see a horse jumping with bascule, except for some promising unbroke horses being chased over jumps in a sales video? 🙂

The point being, what you saw probably wasn’t any closer to correct (that which improves and protects the horse’s health) than what you’d see in any other discipline.

Interestingly, today my facebook feed had pictures of Ashlee Bond’s winning ride in the Grand Prix at Thunderbird (B.C., Canada) yesterday. Including an action shot showing stretching forward into a following contact over the large jump (photo is a touch before the apex of the jump but I’d be willing to bet the horse was in a lovely bascule at the peak) and a shot showing the horse reaching down for a stretch into longer rein while trotting out of the ring.

Although it’s a very different head positioning than you see in dressage, good jumpers are ridden into contact and with a lot of collection and extension and often creating a very big difference in the horse’s stride. Good jumpers change quickly from a short, coiled, power step to a long, ground covering step very quickly.

But, if what you were watching was of the “amateurs with money to buy nice horses” variety, then (speaking in generalities obviously, there are exceptions) that sort of person is mostly buying a quality horse with scope to spare for what they want to do, and they’re riding the horse within what comes to it fairly naturally. So they get by without doing the serious training that would be required to develop the horse to its full potential.

Link?

I wish I had an easy way to post it but my computer has facebook blocked as it’s a work machine and I can’t get the link to post from my phone… but the action shot is on the facebook page of Rocky Mountain Show Jumping, will be one of the more recent posts, and the stretching trot picture is on the facebook page of Thunderbird Show Park.

Rocky FB: https://www.facebook.com/RMSJ.Calgary?fref=ts

Thunderbird FB: https://www.facebook.com/thunderbirdshowpark?fref=ts

if that will work, its a short clip, clearly there is a martingale limiting full use of neck, and plenty of inverted moments, and a time coming around the turn when the horse was clearly thinking ‘I’m outta here”. Jumping 5-6 feet with big spreads is challenging, pretty much the limit of ability of even the select horses that show grand prix. It is also clearly the limits of riders communicating smoothly to horses instead of having to sit back and hang tight to obtain the adjustments necessary to get the horses in position to take the next jump. If a talented horse with a talented rider can’t ride at least half of the course without an ‘argument’ that requires turning the horse upside down to get ‘compliance’, is it a sport that needs rethinking? And this could apply to most horse sports.

Adding here to jrga’s comment: I want to introduce an analogy (while not perfect, I think the point will be clear); horses use speed to clear obstacles that start to tax them – analogy coming up – much in the same way a driver would use speed to jump a car a bigger distance, when the car lacks horsepower.

We know that speed requires a horse to shift its weight onto its forehand and become hollow. (If you don’t know that, there are a number of articles on this blog that talk about it, starting with Speed Kills).

On the other hand you’ll hear people all the time talking about collecting the horse/getting the haunch under the horse for it to clear higher and larger obstacles. We know to achieve the latter the horse has to shift its weight to its haunch and round.

What we often seen in the show ring nowadays is more of the former; speed being added to compensate for a lack of horsepower. And when you add speed, you decrease the amount of bascule (and the ability to steer and control the horse). This gets you a whole lot of head up in the air, fight for control, kick and yank.

On the other hand, just dropping money on a saddle doesn’t guarantee fit either, Two people in our barn have each dropped upwards of $6,000 each on a currently-popular Canadian brand of dressage saddle, which has only one tree style, but “guarantees” its local reps can fit any horse. A year later and they are still struggling to get a fit, for horse and for rider.

just pick some videos from the internet and watch how much time a jumper spends inverted as opposed to neutral or rounded as it goes around a course. This one I picked because it was relatively short, 5 mins. 40 secs., a jump off with some recognizable names for a $100,000 purse at grand prix in US, so no big time international names.

There is a lot of just holding the horse back, these jumpers need to be goers, but if they won’t accept an adjustment quietly to get the distance and placement on the jump the rider wants, then ultimately they will be fighting, bucking (please see the first horse) throwing their heads and going hollow, which isn’t the best way to get a good clean round out of a horse.

I Googled Ashlee Bond and found some gorgeous photos, though not the ones linked here. I’m not sure how often I’ve seen a horse jump like that, in real life. When I go to spectate at the big jumps at Thunderbird, a lot of the horses seem to be heaving themselves over, straight up and straight down. And I’ve never been up close to anything over 3 feet until the other day. Most horses don’t really use themselves much at 2 foot 6″! I’ll need to download my snapshots from that day and see if the horses had bascule. I do think the girl I watched most, over the 5 foots, was a contender, and was off to Spruce Meadows soon, but I have no idea of her rank at that level.

I like the fact that jumpers go around with natural head carriage; it’s a relief from seeing the dressage wannabes at my barn riding around with full body weight on their horses’ faces. But I’m thinking that jumpers ideally need to do more work than that, to build up the topline. This would help protect against the moments in the jump ring when they do inadvertently invert. Of course some jumpers are racing around inverted the whole time, especially at the lower levels, but that’s just yuck.

OK, just saw the video of Ashlee Bond that jrga posted. Interesting in that it had the bascule over the actual jumps that the still photos captured, but some rough moments between jumps.

A few years ago we discussed here my Paint Mare’s shoulder, and Mercedes pointed out that though she was trying hard to fold her knees over small jumps, she wasn’t really getting her forearm quite high enough, and was twisting her legs slightly. This was because her humerus, while long, wasn’t quite as upright as it needed to be.

So since then, I’ve been casually but consistently evaluating every photo I’ve seen of low jumpers (under 3 feet) including all the “super talented scopey jumpers showing 2 foot 6 and schooling 2 foot 9” for sale. I have yet to see a photo of one actually tucking at all, rather a lot of hanging fore-legs. How would you evaluate this? if the forearm is horizontal but the cannon bone is hanging straight down, is this more promising than if the knees are tucked, but the forearm isn’t quite horizontal? Or would a good jumper have both the desire to fold and the ability to gt the forearm high from the start?

I also remember it was said here that getting the wrong distance to a jump could affect the knee position as well.

Of course I realize that horses aren’t actually putting much effort into jumps at this height. Also most of them don’t really have optimum jumper conformation. I have to say, I was puzzling a bit about the “long and upright humerus” criterion, because although I understood the idea, I felt like I wasn’t seeing much difference in actual horses. Then I went to see the big jumpers school, and I saw what a good jumper front end looks like, and I saw that it was quantitatively different from anything I’d seen before, like seeing a totally new breed of horse.

So many things can affect jumping form. Another reason for a horse not lifting those knees and getting the forearm at least parallel is tight neck or shoulder muscling caused by – you guessed it – always being ridden on the forehand and/or being longed/ridden in side reins, draw reins, btv, etc…

Yes, being long on takeoff, or chipping in is going to affect form. Yes, how the jump is built; vertical, oxer, staircase construction can alsso affect form. Yes, a balanced rider versus being left behind versus leaning over the horse’s neck will affect form. Yes, releasing, following the horse’s mouth or not will affect form. Yes, the amount of effort the horse needs to use or naturally uses given the size of the obstacle will affect form.

However, a horse with the right kind of conformation is going to show they can get those knees up and those forearms at least parallel to the ground even over small stuff.

Those tires I believe were 24-26″. There is a small, shallow ditch in front of them. Excuse the uneveness of the front legs and the lean. He was longeing on a smaller circle, so take off was from a tighter arc and he’s anticipating the same tight arc right on landing.

http://i878.photobucket.com/albums/ab348/HoovesBlog/Tires_zpsxwqbwxvz.jpg~original

Again on a circle, but a bit bigger so coming in straighter and therefore more even with the front legs. This is just 3′ 3″.

http://i878.photobucket.com/albums/ab348/HoovesBlog/Jump_zpsk32fwn7d.jpg~original

Point being, a horse has the ability conformationally or not and will show it even on lower stuff or when circumstances aren’t perfect.

OK, if I’m reading you right, as I thought: the ability to get the knees and forearms up is the key thing, and folding is going to come as they need it over higher obstacles. I suppose if a horse in training is getting its forearms up at least part of the time, that’s an indication it has the abiility even if it isn’t choosing to use it all the time?

First they have to have the range of motion in the joint/s and a good amount of that comes from the humerus bone – length, orientation (vertical vs horizontal) and thus the shoulder angle. Typically if they do, they will show a natural proclivity for lifting the knee and bringing that forearm at least parallel (without twisting) even if everything else isn’t right and proper.

Twisting often happens because the horse can’t get the knee up and/or the lower leg tight (naturally) and knows it, and also knows it needs to try and clear the obstacle.

Specifically related to Paint breed horses, they often have closed shoulder angles, more horizontally set humerus bones, and shorter humerus bones, which will prevent knees up, horizontal forearm and tight lower leg form.

I love Mercedes blogs. Wish I had found them 15 years ago. I’m 92 now. quit riding two years when my last mare died.