After breaking down the structure of the equine neck in Part 1, it’s now time to look at our original sample group of six horses to see how their necks measure up.

Horse #1 – 10yr old QH Stallion

This fellow has a medium length of neck. It could be a bit longer and it wouldn’t hurt him, and it could be a bit shorter and it also wouldn’t hurt him; and ‘that’ references not hurting him athletically. His neck is also set with a medium depth.

In terms of height of neck set, we can see that his lower cervical curve is quite high in relationship to his scapulae, and therefore he has a high neck set. Even though he’s standing in a chill manner, we can still see evidence of correct development of the tubular complexus muscle; that is be partly due to him being a stallion and a stallion’s natural tendency to telescope the neck as a means to ‘get the ladies’, but it’s also due to the underlying bones. This is a beautiful equine neck in terms of structure, usability and athletic performance.

Horse #2 – QH Gelding

Our second QH has a shorter neck than our first, most significantly shorter in the upper cervical curve (a fraction shorter and we’d have to call him hammer-headed, and I wouldn’t argue with anyone who wanted to call him that now) and through the middle segment. You can see that that shorter upper curve causes the horse to have less room through the throat latch area. Fortunately, this boy also has a high neck set, so the ability to use the neck correctly is there. In training, there should be focus on stretching the neck correctly so that those little muscles and ligaments behind the poll and ears are made as long and supple as possible. As well, we’d not expect or ask this horse to come as tightly onto the vertical.

Horse #3 – 4yr old QH

It’s more difficult to examine this horse’s neck due to the angle of the photo. His neck is proportionately medium in length, with a medium depth of set. In those regards he’s much like our QH stallion. He is quite different, though, in height of neck set. This is a low set neck at midpoint of the scapula.

On the plus side, the person training this horse has done an excellent job of preventing this horse from excessively dropping his base of neck and creating the typical inverted neck muscling so often seen, but we can see how this low set neck puts additional weight down and forward onto the front end. While both the QH stallion and this one are clearly downhill built, the stallion – with his superior structured neck – can easily lift his base of neck and the rest of his front end up, while this horse is stuck in perpetual ‘down the hill’ motion. Further evidence of being stuck on his forehand can be seen in the muddy shoulder bed and the lumpy, excessive muscling covering the shoulder.

Horse #4 – Arabian Stallion

This is a neck on the longer end of the scale. We wouldn’t want it to have any more length. Like most Arabians, the actual bone structure underneath is quite good. This is your classic arched neck and it’s beautiful and highly functional.

Horse #5 – TB Gelding

This neck, imo, is a fooler. There’s a ‘double bulge’ in the lower cervical curve that shouldn’t be there. This is typical of a horse that is out of alignment.

If we take the lower bulge and compare it to the scapula this horse’s neck set is right at the mid-point, making it a low set neck exactly like our grey QH, and it just simply is not, while the upper bulge is located too far forward to be correct, making the set fall in the medium to medium-high category, which it is not.

Therefore, I’ve split the different between the two bulging points to establish a medium to medium-low set, which is a more accurate representation of this horse’s neck. It is set on better than the grey QH’s, but it’s still set on at the lower end of the scale.

In terms of length, this neck is bang on and the horse has a very good upper curve and middle section. With correct riding and training (after the neck is fixed), the musculature and posture of this neck could be improved substantially.

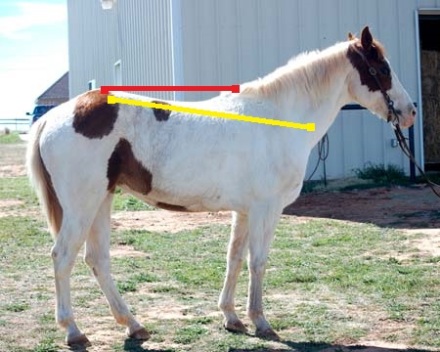

Horse #6 – Paint Mare

Here we have a classic bull neck with its short upper curve resulting in a hammer-head, its short middle segment, and its long, wide lower cervical curve creating an unattractive bulging of that part of the neck. Its overall length is short.

We are almost done examining out sample set of horses, just the hind legs to go!